Recognizing that karma is essentially imponderable, the Buddha refused to discuss its intricacies or the way it unfolded in one’s life. He spoke of the cause-and-effect relationship between actions and consequences and emphasized the value of mindful scrutiny of each thought and behavior in controlling negative karma, but beyond this, he avoided abstract discussions on the issue. Why is karma so inscrutable? The foremost reason has to do with the unity of life and the impossibility of explaining unity from the perspective of separateness. When we are acting from the delusion of self, our motives are not in concert with the rest of creation. Blinded by desire, we in effect act “alone” against the whole, and frustration and suffering inevitably result. The metaphors offered below can be helpful in gaining some understanding of this important but enigmatic subject.

Electricity If we are working carelessly with wiring and we get shocked, we are unlikely to think that the bolt of electricity was punishment from God for our negligence. Rather, we see right away that we have no one to blame but ourselves. Certain behaviors are paired with certain predictable consequences. If we are not careful in the way we handle live wires, we will learn hard lessons in the process. It is simply the nature of the work. Similarly, esoteric spirituality emphasizes personal responsibility rather than ideas such as sin and divine judgment. Karma is called the great teacher, and while its consequences can be dire, it is through the pain and suffering our mistakes produce that we ultimately become seekers on the path to freedom.

Ceiling Fan Those of us who live in warm climates often have ceiling fans that quietly, but efficiently, circulate the air and make our homes more comfortable. When the fan is turned off, the motor stops propelling the blades, but they continue in their circular motion for several minutes before they come to a complete stop. It is the same with karma. Even when we are able to refrain from behavior that has produced suffering for us in the past, we may not find ourselves immediately free from that suffering. The momentum of our previous actions must often play out in our lives before the fruits of our new behavior become apparent.

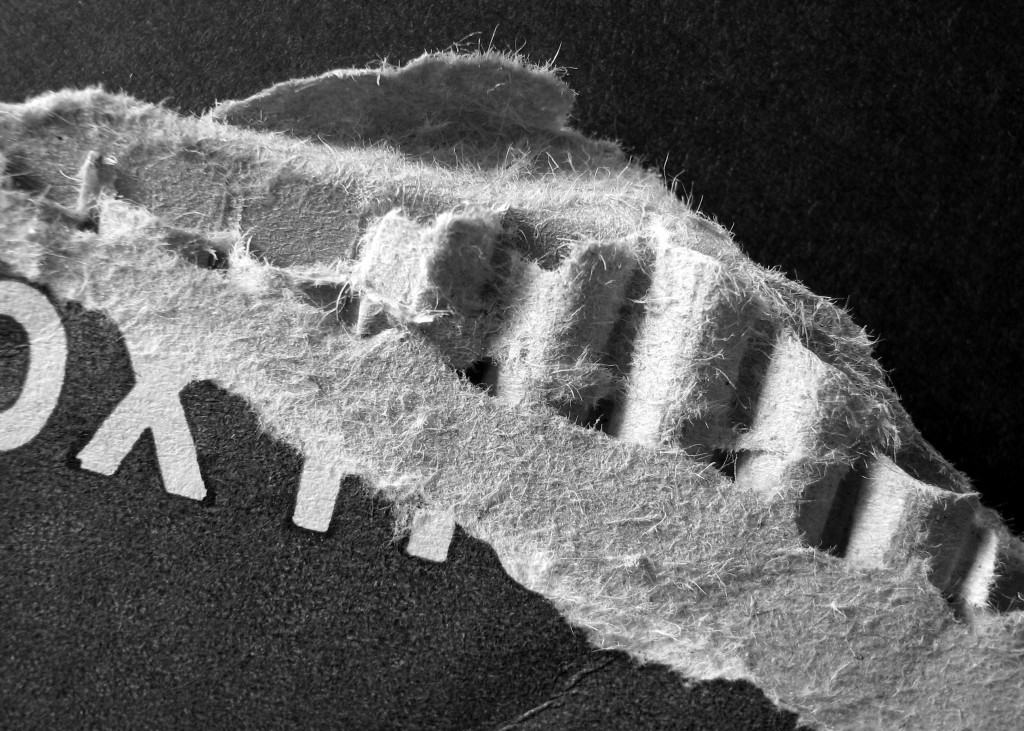

Spiderweb Spiderwebs have decorated the nooks and crannies of our lives as long as any of us can remember. The delicate interweaving of the silken threads is designed by nature to alert the spider to the slightest disturbance. If the web is touched in any part, the entire structure vibrates. The world we live in is similarly intertwined. Nothing is separate, and a disturbance in one area is felt throughout the whole. The principle of karma is based on this kind of reciprocity and balance. Our individual behavior does not occur in a vacuum, and no matter how insignificant our actions may seem, they produce an effect in the world around us.

Factorial When we are suffering, we often want to isolate the causes and identify the sequence of actions that led to our current conditions. We continually obsess over particular actions, our own or others’, as the genesis of our personal and societal problems today. But nothing is that simple. Consider factorials—mathematical calculations of the number of ways in which a certain number of things can be sequenced. The factorial for 10 exceeds three and a half million possible sequences! If just ten physical objects can be sequenced in so many different ways, it should be obvious that any attempt to analyze the karmic chain of causation in human behavior is futile. Everything causes everything; even the minor daily events in our personal lives are infinitely complex.